Making a case for Meg, Beth, or Amy March takes imagination, generosity of spirit, fortitude. Making a case for Jo requires no such talents. If you ever felt “homely and awkward and odd and old,” you probably already love Jo. If you preferred books to living people, you probably already love Jo. If you were called a girl but wanted to be a boy, you probably already love Jo. If you “carried [your] love of liberty and hate of conventionalities to such an unlimited extent” that you drove away those closest to you, you probably already love Jo. And if you are reading this, you almost certainly already love Jo.

But being so beloved would undoubtedly surprise Jo. When starchy Meg grumbles, “November is the most disagreeable month in the whole year,” Jo retorts, “That’s the reason I was born in it.” Jo is roiling with anger for most of Little Women, and she believes her anger pushes her outside of the economy of love the novel itself so lovingly describes. Why is Jo so angry? Where to start? Because, as she says, “I just can’t get over my disappointment in not being a boy”? Because the ungainly body she does have contrasts painfully with those of her lovely sisters? Because when she cuts off her long hair to earn money to care for her ailing father, her sisters, who should be awestruck at Jo’s generosity, reproach her instead? “O Jo, how could you? Your one beauty!” Their genuine belief that she has consigned herself to oblivion is brutal, but worse is the way the novel becomes an echo chamber for the cruel phrase. Other characters, including the narrator and Jo herself, repeat verbatim the statement that Jo’s hair is her “one beauty” until it gains the force of fact.

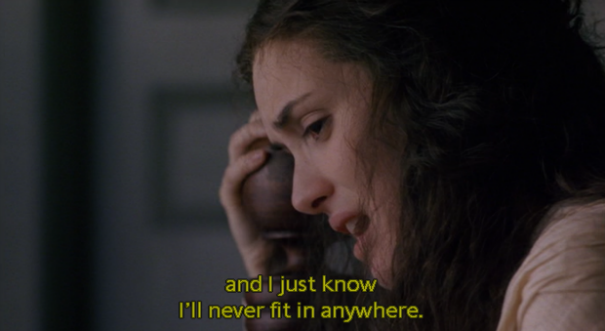

If Jo has plenty to be angry about, it is all the more infuriating that Little Women is in some way the story of how she learns to discipline that anger. But the way the novel judges Jo puts readers even more squarely on her side; we love Jo’s anger all the more fervently because it will not. After Amy has burned Jo’s cherished book manuscript, and Jo in return has shaken Amy “till her teeth chattered in her head” and then nearly let her drown, Jo desperately unburdens herself to Marmee. “You don’t know, you can’t guess how bad it is! It seems as if I could do anything when I’m in a passion; I get so savage, I could hurt any one, and enjoy it.” Jo’s confession of not only her anger, but also the pleasure she takes in it, endears her to the reader raging against the world and its demands, including the demand to not be so angry.

If Jo has plenty to be angry about, it is all the more infuriating that Little Women is in some way the story of how she learns to discipline that anger. But the way the novel judges Jo puts readers even more squarely on her side; we love Jo’s anger all the more fervently because it will not. After Amy has burned Jo’s cherished book manuscript, and Jo in return has shaken Amy “till her teeth chattered in her head” and then nearly let her drown, Jo desperately unburdens herself to Marmee. “You don’t know, you can’t guess how bad it is! It seems as if I could do anything when I’m in a passion; I get so savage, I could hurt any one, and enjoy it.” Jo’s confession of not only her anger, but also the pleasure she takes in it, endears her to the reader raging against the world and its demands, including the demand to not be so angry.

And stunningly, Marmee replies, “I am angry nearly every day of my life, Jo.” Now this is something worth hearing. Gentle Marmee, too, is a cauldron of rage? Finally it seems someone might recognize Jo’s anger and will reflect it back to her transfigured, as a wide-awake understanding of ordinary injustice. But no. Anger is useful, Marmee explains, not as a means of knowledge or change but as an opportunity to practice self-control. The answer to anger, as to everything in the March household, is to work; “work is a blessed solace.” Perhaps there is no more heartbreaking moment in the novel, Beth’s death included, than when Jo gamely tries to follow Marmee’s advice by writing a paean to housework called “A Song from the Suds,” which touts how “anxious thoughts may be swept away, / As we bravely wield a broom.” In other words: if you’ve noticed how shitty it is to be a woman, then deal with it by doing more of the shitty things, like cleaning and smiling, that women are asked to do. Maybe you’ve heard this song before, or some version of it.

But Jo is angry, above all, because she gets the bitter tragedy of Little Women as no one else in the novel does. It tells a story about the bonds that knit together a family of women — of love nurtured with exquisite care — only to break up that family and transfer its bonds to an array of frankly disappointing men. (Even Mr. March’s return from the Civil War must be counted among these intrusions, although Alcott does her best to recover by more or less forgetting him.) Alone, Jo recognizes what Brian Connolly describes as the “erotic excess” that suffuses the nineteenth-century sentimental family as it devotes itself to the cultivation of love within the home circle. If they were “all boys, then there wouldn’t be any bother,” she observes; homosociality and endogamy would be on their side. But as girls, their love is manufactured only for export, to enrich the emotional lives of men.

As a writer herself, though, Jo knows Little Women is really a love story about the Marches. And every nerve in her freakish body tells her that it is treachery to bend that love otherwise. Thus while Alcott would save her actual incest romances for other novels, particularly Eight Cousins and Rose in Bloom, Jo feels the family romance’s force in Little Women, and no Hail Mary pass at her from the meddling Professor Bhaer can erase that. “It isn’t pronounced either Bear or Beer, as people will say it, but something between the two,” she tells her family. It’s pronounced “beard,” of course: Jo’s attachments are already formed, and they are for her sisters.

So I do not think Jo is joking when she says of Meg, “She gets prettier every day, and I’m in love with her sometimes.” She certainly doesn’t let the idea go. “I just wish I could marry Meg myself, and keep her safe in the family,” she declares when John Brooke starts sniffing around, leaving his damn umbrella in the doorway. Anyway, Jo can play that Freudian game as well as he can, if not better. Just watch her “put her hands in her pockets” and whistle when Amy tells her she’s too boyish, or “bounce way on Ellen Tree.” Jo obviously has the most game in the whole novel.

Or watch her on the “family sofa” with her best friend Laurie, whose professions of love she spurns because he is a “brother” to her. (We could understand her protest to mean that brotherly love is sexless, but we could also understand it to mean that erotic love should be contained in family relations, not estranged in marital ones.) Jo’s favorite spot is a corner of the sofa, where she appropriates as her “especial property” a “repulsive pillow”: “hard, round, covered with prickly horsehair, and furnished with a knobby button at each end.” By the time they are grown, “Laurie knew this pillow well and had cause to regard it with deep aversion, having been unmercifully pummelled with it in former days when romping was allowed, and now frequently debarred by it from taking the seat he most coveted, next to Jo in the sofa corner.” Are you with me so far? Jo’s “especial property” is a “repulsive,” “hard,” “prickly” pillow, which she uses to beat Laurie or to prevent him from getting too close when they’re on the “family sofa.” Wait, did I mention this pillow is called “the sausage”?

Or watch her on the “family sofa” with her best friend Laurie, whose professions of love she spurns because he is a “brother” to her. (We could understand her protest to mean that brotherly love is sexless, but we could also understand it to mean that erotic love should be contained in family relations, not estranged in marital ones.) Jo’s favorite spot is a corner of the sofa, where she appropriates as her “especial property” a “repulsive pillow”: “hard, round, covered with prickly horsehair, and furnished with a knobby button at each end.” By the time they are grown, “Laurie knew this pillow well and had cause to regard it with deep aversion, having been unmercifully pummelled with it in former days when romping was allowed, and now frequently debarred by it from taking the seat he most coveted, next to Jo in the sofa corner.” Are you with me so far? Jo’s “especial property” is a “repulsive,” “hard,” “prickly” pillow, which she uses to beat Laurie or to prevent him from getting too close when they’re on the “family sofa.” Wait, did I mention this pillow is called “the sausage”?

So once Laurie begins to insert himself between Jo and her sisters, instead of just contributing to the general romping as he did when they were children, she brandishes the sausage. Yet the amazing thing, the really heartwarming thing, is that Laurie gets all this and accepts it. One evening when he tries to get next to her on the sofa, Jo raises the sausage against him and it vanishes: “coasting onto the floor, it disappeared in a most mysterious manner.” But I think we know exactly where it went. Always “so generous and kind-hearted,” Laurie takes Jo’s sausage, and he goes and fucks Amy. “He consoled himself for the seeming disloyalty by the thought that Jo’s sister was almost the same as Jo’s self.” Luckily for Jo, Laurie is also almost the same as herself; no less an authority than Marmee said so when she warned against their marrying. So when Laurie first drops a reference to Amy as “my wife” in front of Jo and she interjects, “Aren’t we proud of those two words, and don’t we like to say them?” you could hear her “we” as sarcastic, but you could also hear it as sincere. Jo gets to enjoy the pleasure of wedding Amy as well as Laurie does.

Whether you identify with Jo from the first page or not, the experience of loving Little Women aligns you with her desires. For the novel teaches us to want the same things that she does: that the Marches might stay the Marches forever, and that we might stay together with them forever. Despite all Little Women’s betrayals, in the end we sing out with Jo, “I do think that families are the most beautiful things in all the world!” If you think that this is the novel at its most mawkish, listen again for the note of protest. It is not so much the world’s already existing families this sentiment celebrates as the family ties this world breaks, denies, and withholds from us.

Lara Langer Cohen: Still not a player.

[carousel category=”littlewomen” count=”4″ columns=”4″ title=”show”]

[…] Meg’s woman’s work is to balance her own competing drives with the loving emotions that, as Lara says, has been “manufactured only for […]

Incest in the Rose books?! Where?

I assume because Rose is courted by her first cousins and eventually marries one? Back in the day that wasn’t incestuous, though.

It still isn’t necessarily, depending what you consider incestuous. Where I live it’s been legal since the 16th century. It’s not common, but it doesn’t squick me out like it seems to with a lot of US people – though I believe the incest laws differ from state to state?

OMG, what a stretch.

[…] course, even when we know this about Marmee, it’s still often hard to know it. What is it about parenting that makes it feel […]