In honor of the publication of Arielle Zibrak’s Avidly Reads Guilty Pleasures, Avidly is running a series of essays on “Pleasure-y Guilts” — “The special frisson that comes from leaning in to the pleasures for which the world makes us feel guilty.” Enjoy! — Ed.

It’s an early spring morning and I’m in my childhood bedroom. I’ve recently shaved my face because my mom doesn’t like it when I have a beard, and I am flailing about my bedroom like a frenetic beaver, dancing it out to Taylor Swift’s “Shake It Off.” I catch a glimpse of myself in the mirror, struck by the way this moment contrasts sharply against the many years I spent in the same bedroom; crying alone to Taylor Swift.

As I mime the ‘hella good hair’ line of the bridge–replete with the accompanying dance moves– my mom appears in the doorframe: “Aren’t you supposed to be a guy?”

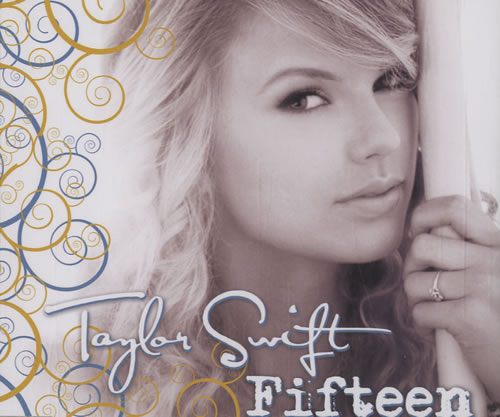

Like most people, I’ve regressed a bit in quarantine. I’ve been delving deeply into Taylor Swift’s discography, a difficult project to resist, given her flurry of productivity this past year. With T. Swift as the soundtrack, I’ve spent the last few months kicking around particular fragments of my adolescence, caught up in the introspective melancholy offered on folklore. When Taylor Swift released Fearless for the first time in 2008, I was fifteen. Much like her narrator in the song suggests, there was a lot I didn’t know at that age. First, that I’d spend most of my life at war with myself over my gender. Second, that Taylor Swift, perhaps paradoxically, would be the soundtrack to most of it.

Growing up as a closeted trans man meant that I felt abroad in my own body for most of my life, while simultaneously yearning for a youth that never could and never will exist. It feels similar to how Svetlana Boyn describes nostalgia: not merely as a reflection of the past but also as a forward looking endeavor. The fantasies of that past, for Boym, are determined by the needs of the present, ultimately having a direct impact on the realities of the future. Although I knew with more certainty than I’ve ever known anything that I was a man, I resigned myself to living as a woman. Which is to say that I can imagine — but not necessarily access — a time in which I have been both the ex-man with the new girlfriend and the woman who is furious about it.

Writing about white masculinity is difficult for a lot of good reasons. As a trans man, I am forever in the process of assuming a kind of masculinity that renders me legible as a man without wedding myself to toxic tropes. Having been socialized as a woman for the first twenty-four years of my life means that I get to choose the type of man I want to be in a way that is never really afforded to cis men. This is, I think, one of the most threatening aspects of the transmasculine identity. While trans men are in some ways just as flawed as their cis counterparts, we are proof of the fact that most of what society thinks of as innate with regard to masculinity is in fact taught.

I have learned — having always been a Swiftie, but still very much in the process of apprehending masculinity — that many men worry about whether or liking Taylor Swift transcends a guilty pleasure and is instead indicative of some greater underlying thing — not a guilty pleasure but just a guilt. A quick perusal of the r/TaylorSwift community boasts many threads on the subject: am I [gay? weird? creepy?] for being a 34 year old straight white male who loves Taylor Swift? Will my girlfriend think it’s odd that I like Taylor Swift? Is it okay for me (38/M) to take my daughter to a Taylor Swift concert?

What this line of thinking evinces for me is not only that my fellow male Swifties are worried about what a potential like (or even love) of Taylor Swift’s music might mean, but that there is an element of guilt deeply imbricated within our understandings of taste and how they relate to a perceived type of manhood. The irony here is that I would argue that Swift herself is often crossing, if not blurring, the gender binary in her writing; not only when she is changing the pronouns in her songs. I think that this is in large part why her work is as legible to me as a twenty-eight year old man as it was to me as a fifteen year old girl.

As an artist, individual, and business, Taylor Swift has been the recipient of a lot of ire. Some of it is well deserved and some of it rooted in some deeply misogynistic vibes. Indeed, Swift does manufacture and sell a particular type of youth, one that is overwhelmingly white and heterosexual and middle class. But for me, at least in retrospect, it was also somehow undeniably queer.

I think of myself again in my childhood bedroom — at 15, or 18 — thumbing back the click wheel on my iPod to re-listen to “All Too Well” while navigating the breakups of nascent relationships that perpetually stalled out not in the least because I was never myself when I was in them. Or more recently alone at home in Philadelphia at 28, belting along to “mirrorball” in the shower, feeling acutely what it’s like to be preoccupied with the pursuit of a perpetual almost.

At the heart of my guilt, then, I suppose, is the way that Taylor Swift sutures me to my feelings. I am not ashamed of the deep joy or profound solace that Swift’s music brings to me. But her admissions and ruminations are so unashamed and raw. They provide insight into a rich inner world that I only wish I could access. Her commitment to producing work so deeply rooted in the affective often presents me with a challenge, one that requires a continual rethinking of my own self-imposed limits of masculinity.

Jay Jolles is cruisin’, can’t stop won’t stop groovin’ to Taylor Swift