I have read and taught Little Women more times than I can count. I’d be lying if I said that it always surprises me when I read it again. It almost never surprises me. It’s one of the novels I know best, and there is not a line in it that I don’t remember encountering and responding to, even the ones that grate on me. The prissy, fluting authorial interjections are particularly painful. The lisping baby talk of the thoroughly objectionable Daisy and Demi are unbearable. But the most maddening element, even after all these years, is Beth. Little Beth, trotting back and forth in the March house clutching her dustpans and ruined dolls, dreaming her dreams of the ever more useful dustpans and more severely injured dolls that will surely await her in her heavenly home. Little Beth, loved by everyone. Except me.

The book is a pretty good index of how I learned to read literature over the years. I could tell you in minute detail how I learned to move from identifying with characters to thinking about structure in narrative, but that’s boring to everyone but me. If I had a therapist, I wouldn’t even talk about this with her, although I would probably have the sort of therapist who also read Little Women as a child, and we would clearly agree that some reasonably useful diagnoses of one’s psychic life could emerge from discussions of the characters.

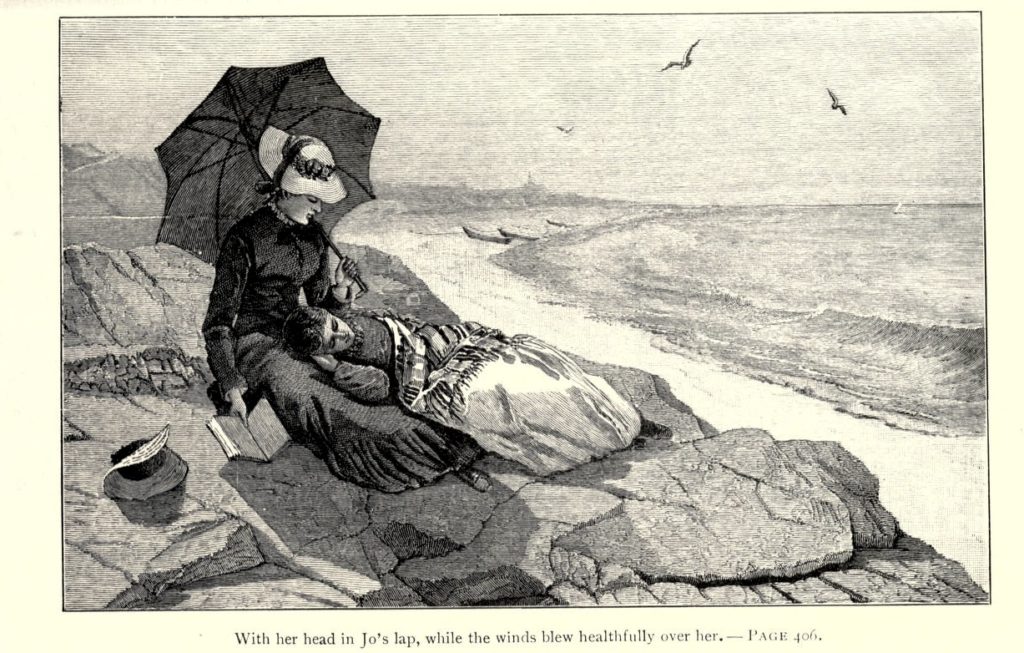

Except we wouldn’t have much to say about Beth, though we would agree that we could still be brought to tears by thinking about her death. I am perfectly willing to cop to that; I cried as a girl when I read it, and I cry as an adult. Real crying, too — not just that pleasurable melancholy wistfulness and faint quiver in my voice that I usually shorthand as crying at a book, but flushed face and sobs and tears and ruined eyeliner.

I resent and am puzzled by my tears about Beth’s death scene — the truth is, I can hardly wait for her to go. But my tears are not tears of relief. They are not tears of frustration. They’re real tears, but how is that possible? It’s not the most moving death scene I’ve ever read, and Beth is, even when she is dying, pretty forgettable. Except for a short, horrifying blip of suffering at the end when you understand the physical, rather than the familial, violence her death entailed, it’s aggressively saccharine. Actually, it’s more saccharine even than Beth is — you can’t fault Beth for ostentatious piety. That would, after all, be the mark of character and personality, like Amy’s delicious vanity, or Meg’s studied affability, and character and personality is precisely what Beth doesn’t – and can’t — have.

I resent and am puzzled by my tears about Beth’s death scene — the truth is, I can hardly wait for her to go. But my tears are not tears of relief. They are not tears of frustration. They’re real tears, but how is that possible? It’s not the most moving death scene I’ve ever read, and Beth is, even when she is dying, pretty forgettable. Except for a short, horrifying blip of suffering at the end when you understand the physical, rather than the familial, violence her death entailed, it’s aggressively saccharine. Actually, it’s more saccharine even than Beth is — you can’t fault Beth for ostentatious piety. That would, after all, be the mark of character and personality, like Amy’s delicious vanity, or Meg’s studied affability, and character and personality is precisely what Beth doesn’t – and can’t — have.

There’s no Beth there at all. She slips into rooms and out of them, she lets out little sighs no one hears. When I am reading about her, even when I follow every word, I tend to skip over her like I skip over Jo’s poetry (pausing, of course, to note that Beth inspires the worst of it). Beth never burns up stories, fries her bangs with a curling iron, drinks too much champagne, goes off to New York, or sleeps with a clothespin on her nose. She did kill her bird by accident, but that occasioned a small poem by Jo so to my mind it’s a crime overshadowed by an even greater one. (And anyway, Beth is surrounded by cats, so it was hard to see how the bird was going to make it very long). She’s more idea than character, never less real than when the text suggests somehow that she’s like the other sisters and walks, and talks, and eats.

When I teach the book, I find myself falling back on the autobiographical and historical explanation, as if somehow that could explain the unearned sorrow Beth occasions from readers, and from me. This book, I tell them, is autobiographical; Louisa May Alcott’s sister died. Sometimes I rattle off statistics about mortality rates, and then remark that sentimental and beautiful death scenes are like a thick floral bouquet over a rotting corpse; a way to disguise the hard fact of protracted, lingering illness. Beth then comes into view as an historical sign or a neatly stitched up psychic wound.

Yet even as I give this explanation, I have to brush away some discomfort — the discomfort of producing cheap historical factoids to answer a narratological question about why some characters are round and some flat, the nagging sense that in giving such an answer I am undoing everything interesting about reading the novel, the suspicion that I would rather not talk about Beth because there is nothing to talk about. Or rather, that I do not know how to talk about her. She’s only useful to talk about Jo, or Amy, or scarlet fever, or consumption, or religion.

Beth irritates me in some formless way — her shyness, her kindness, her tenderness toward the household at large, her complete unavailability for analysis.I can barely visualize her in my head (which is why, incidentally, the casting of Eve Plumb as Beth in an ill-conceived movie of LW was impossible to swallow. You don’t give that role to an actress best known for her resentment of her more interesting older sister).

But I’m always undone by Beth’s things: by the objects that surround and define her. I know a lot about Beth’s stuff. Unlike Beth the person, I can see her stuff quite clearly. I’m not talking here about the things that all the girls have that characterize their quirks and ambitions — Jo’s rakish writing cap, or Meg’s too-tight high heels, or Amy’s turquoise ring — but the things that are her entirely. Her sisters’ things are metonymic; Beth’s are synecdochic. The needle that is “so heavy,” the little piano with yellowed keys, the weird little collection of broken dolls she keeps in a doll hospital, the work basket that is saved and kept in its place after she dies, the mop and dusters that are magically imbued with her presence, the heart’s ease slippers she gives to Mr. Laurence.

I wish I could summon up a little bit of snark here, but the thing about Beth is that her things kill me. I am maddened by her blankness, her unavailability, her inhuman changelessness. I’m annoyed by even the fact that she doesn’t take the laws of fiction seriously enough to pretend to be a real person – she admits as much when she declines to make a castle in the air as her sisters do.

I wish I could summon up a little bit of snark here, but the thing about Beth is that her things kill me. I am maddened by her blankness, her unavailability, her inhuman changelessness. I’m annoyed by even the fact that she doesn’t take the laws of fiction seriously enough to pretend to be a real person – she admits as much when she declines to make a castle in the air as her sisters do.

But her things speak in the voice we never really hear from her, they have will and an intent, they attain a hovering presence she herself never achieves. Beth herself is withdrawn and wasted, and yet the agency of her possessions is not. I look at them as Jo does, with sadness and pity and tenderness (but not with poetry, because no). But these things, powerful as they are, speak most to what Beth is not allowed to be.

At the last, when she is trying to set a beautiful example of the limits and possibilities of reading, I find myself wishing in my heart of hearts that she might finally find a more interesting home in different type of story, a sensation novel rather than a sentimental one. If ever there were a family that needed haunting, it is the Marches. I like to think of Beth not as an absence but as a ghost, moving her family’s things and stealing their clothes.

Stephanie Foote: Will think of a better byline 15 minutes from now

[carousel category=”littlewomen” count=”4″ columns=”4″ title=”show “]

I’ve never quite known why I cry over Beth either. But now I am wondering…Perhaps it is that LMA lives with her ghost and maybe without realizing it, has written her as one. Beth’s possessions are memorable because that is all that is left for LMA to live with and consider. She is writing what she knows, and what she knows is the loss of the idealized sister who is now imbued with this faint ghost light of affection. I think it for Jo that we weep. We weep for LMA’s deep loss. <3

I have raced through this sequence of articles and enjoyed them all thoroughly. I wonder if the key thing about Beth’s possessions is that they all suggest activity, in several cases active creativity. As well as doing the domestic labour the others disliked or had to learn painfully, she creates music, embroidery, comfort. All for others. The sense of lost and betrayed potential is stronger in her than in the others, who all settle in the end for what was Beth’s highest wish. The very sentence in which she dies suggests a full circle has been completed, and all that is left is a sense of waste as well as loss.

Oh, Beth was always my favorite! She is the category of the domestic, absolutely embodied, in all its limitedness, blankness, lack of futurity, obsession with small details of material culture, love of comfort, homeyness. How can you say there’s nothing to say about her? Domestic life is the main category of so many 19th c women’s fictional (and real) experience. The fact that Alcott embodies domesticity in a child – and then makes the child die – endlessly fascinating. When we cry for her, we are crying for the fact that a) she embodies things that women should not be made ashamed to love (as Virginia Woolf said, how many dishes have women washed? how many children have they fed? those things matter!) and also b) the fact that she has no future, has never had a future, no castle in the air. Being the perfect domestic subject makes you lovable but leads to nothing that the art-crazed sisters would see as valid.

This is so true! Even her art is the most ephemeral — the sheet music remains, but the performance itself, its lived truth — does not.

Beth can be read as pathologically shy, suffering a mental disorder; she’s too timid to go to school, for example. Social phobia could constrict her imagination & ambitions as well as stifle whatever intellect she was born with.

When I suffered agoraphobia for a few years, it brought Beth into focus for me.

Artistically, it makes more sense for her to be read in other ways: a symbol of death, or crippling domesticity –but I still can see a precise portrait of social phobia there.

Beth is too good to be believable. I, like you, tend to brush over her scenes because she has no personality except being good and shy. She’s boring. Meg and Amy are actually my favorites because I find them the most relatable.