Avidly is pleased to run the second installment of Jane Hu and Jennifer Schnepf’s Deep Sea Cruise about the Mission Impossible franchise. Read their first here.

“I have a way out.” – Ethan Hunt, Mission: Impossible Rogue Nation

Schnepf: Hi Jane! Last time we discussed Tom Cruise and Mission: Impossible we had only four films to consider. Since then, Tom Cruise has not slept in order to promote the newest addition to the Mission: Impossible series–Mission: Impossible Rogue Nation. We both watched the fifth installment last weekend and, not surprisingly, had a lot of thoughts. Many things here felt familiar–receiving missions on vinyl, death and resuscitation, jumping into cylindrical structures. Should I mention this talk will contain spoilers? (But, also, if you know the franchise, are you ever really surprised by it?)

Hu: Remember that time when we waxed critical on Cruise’s meta-persona in his Mission: Impossibles–each installment speaking more aggressively to Cruise’s indelible, well, Cruiseyness than the last? It’s not really a surprise that the latest Rogue Nation is working overtime to outdo them all. And, it’s been clarifying in thinking about what makes a successful film series: you have your James Bonds and the Step Ups–all variations on a theme–and then you have star-driven franchises such as M:I and, in a way, Toy Story in which interest is maintained by each installment improving upon the last. All gears are fully in lock by the time of–and this is a truly mad realization–the fifth installment of Cruise’s M:I in nineteen years. I watched Rogue Nation with with a group of Cruise skeptics and everyone left a convert.

Schnepf: And yet, Rogue Nation is consistent with the early films. For instance, since Brian DePalma’s first Mission, Ethan Hunt has been clinging to things. Gravity and lack of friction fail to loosen his grip. The first time I noticed this, the clinging seemed overwrought. Flattened by the force of the wind, Ethan desperately grasped at the roof of a train as it rocketed through the countryside, bound for the chunnel. Then, in M:I2, he clung to rocky outcroppings, in M:I3 it was a getaway van, and by Ghost Protocol it was the sheer surface of the Burj Khalifa. By then I understood. Ethan clings to negotiate a world that’s grown too fast, too uncertain, too slick.

Hu: Jenn, this IMAGE. Where is the traction coming from? Why isn’t he flying off of the roof of this machine? How much hair gel does it take to keep Cruise’s hair in place, or is that sleek glossy mane simply the product of a very powerful wind machine? Out of context, it really does look like a classic scene on a train (literally) except, wait, Tom Cruise doesn’t simply “ride a train.”

Schnepf: It’s as though Ethan’s extreme clinging habit had been waiting, all this time, for Rogue Nation to come along. At last, all that improbable clutching has culminated in the greatest clinging showcase of our time: Ethan hangs onto the side of an AirBus as it taxis down the runway and takes flight. Even if you haven’t seen the movie, you’ve seen this spectacle condensed into a single image repeated on movie posters and internet ads, billboards and memes. The ready portability of his dangling body reinforces the narrative crafted by the film’s publicity machine to describe the stunt: through a singular force of will, a real professional risks his life to get a job done. Despite its pervasiveness, the account fails to acknowledge what’s apparent in the teaser of the stunt and the opening scene of the film: none of this clinging is possible without collaboration.

Hu: At the same time, Ethan’s superhero clinging is the necessary antidote to the technological task force underwriting all his feats. It takes his team more than a few tries to open the correct hatch for Ethan to climb into the AirBus, and all the while he must–against all physical odds–remain clinging to the side of a speeding plane. What I love about this flashy opening stunt is just how bad the collaboration is. Simon Pegg is manning the controls for the AirBus and it’s all in Russian! He can’t read Japanese and keeps opening the wrong door! As such, Ethan’s old school tactics win against new technology again! The old school intro doesn’t stop there, however. When he does finally get inside the plane, the first thing he encounters is almost a cartoonish throwback: a wall of explosives. It’s not the digitized technological threat of Citizenfour; it’s not a canister of biohazardous material dubbed “The Rabbit’s Foot”; it’s not a tiny sculpture carrying microfilm that carries government secrets. It’s the Cold War threat writ large and literalized in a pile of bombs. Thankfully, Ethan Hunt saves the world just in time, though the world doesn’t necessarily know it. If Rogue Nation had an opening statement, it would be: “Humanity still needs the IMF.”

Schnepf: Remember the iconic cropduster scene in North by Northwest?

When I watched the opening of Rogue Nation I was reminded of North by Northwest because it seems to mirror Hitchcock’s scene (both feature solitary men dashing across the screen in tailored grey suits), and invert it: Thornhill runs away from a deadly plane while Ethan runs toward one. In part, what makes Hitchcock’s scene so terrifying is the sense of bleak isolation one gleans from the establishing shots of the empty horizon and the fallow fields that greet Thornhill. As Hitchcock put it, “The man stands alone.”

Ethan’s life, on the other hand, is always cradled by an invisible, yet powerful, network of care. To underscore this, McQuarrie opens his film with a rapidly branching conference call that links Benji to Brandt at IMF headquarters, before drawing Luther and finally Ethan into a telephonic web of togetherness. Luther, we learn, isn’t even on the clock (as Brandt, the administrator, points out) and yet the four men find themselves fiber-optically bound with the shared purpose of keeping Ethan safe. It’s easy to forget that, like Thornhill, Ethan is physically alone out there. The fields here are fertile, literally a site of friendship’s plentitude (Benji is camouflaged in the them, after all). The team’s virtual presence seems so immediate that Ethan’s dangerous predicament is drained of the menace that Hitchcock’s man-in-the-fields scene aroused. If the opening imparts a lesson, it’s that Ethan’s uncanny ability to convert clinging into survival depends on the kindness of others.

Hu: I love the comparison with North By Northwest, especially as Roger Thornhill is–as Ned Schantz has taught me–one of cinema’s greatest parasites. He is literally running like a bug in fallow field. When the government creates the fictitious character of George Kaplan in order to distract the criminals from the real spy, Thornhill falls accidentally, and beautifully, into the role of Kaplan–even after US Intelligence decide to forego that particular strategy. Thornhill the parasite can live off of literally any narrative–even after those who initially produced it have given it up–and the multiple plots that finds himself tangled in are sustainable insofar as Cary Grant is willing to believe. And, oh, how fiercely he believes. Taken by themselves, however, none of these plots make any sense. It’s what makes Hitchcock’s film so compelling and rewatchable. I’ve seen North By Northwest a dozen times and I still probably couldn’t narrate the plot from memory. In all these ways, it’s kind of like Cruise’s Mission: Impossible. Like North by Northwest, Rogue Nation is a narrative that feeds off of itself. As this most recent M:I makes clear, it is becoming increasingly harder to differentiate the good guys from the bad–the Impossible Missions Force from the alleged Syndicate. Even the hyper-paranoid CIA believes that the IMF is simply perpetuating a crime conspiracy that no longer exists. At the end of the day, then, what is the point? WHY ANOTHER MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE? As Jeremey Renner’s character William says at one point, “This may very well be our last mission, Ethan. Make it count.”

Schnepf: Jane, I also wonder: is the real shadow organization here friendship? I’m struck by the way that the bonds of secret friendship keep this plot together. It surfaces in the dialogue occasionally. When Luther tells Brandt, “You have to understand something. Ethan is my friend,” he’s really saying he’ll work because of Ethan not because the agency recruits him back. IMF is disbanded but these unemployed agents continue to carry out the emotionally-demanding labor of sustaining their personal attachments because, ultimately, this is the groundwork required to fulfill the more familiar agent duties. (Benji’s friendship, for instance, is necessary to track Lane at the opera.) And all this happens without compensation! Affective work is generally marginalized and feminized so it’s interesting that caring labor is so central to this group of men–and to this plot.

Hu: Rogue Nation is Cruise’s most homosocial Mission: Impossible yet! Though the franchise has been steadily following this tack. Cruise’s early career was about playing the leading romantic hero. But after two failed marriages, plus one committed lifelong relationship to Scientology’s David Miscavige, it’s becoming harder and harder to sell Cruise as a sex object. And maybe that’s something he longer wants. The relationship between Emily Blunt and Cruise in Edge of Tomorrow skews far more toward friendship and camaraderie than toward love, even though they ultimately share a kiss. And even in his 80s and 90s films, Cruise’s sexual tension is often more convincing with male characters: Cruise and Bryan Brown in Cocktail or Cruise and Kevin Bacon in A Few Good Men, for instance. Cruise needs heterosexuality to keep up a public front not just in life, but in movies as well. But the last two M:Is have been very explicit in the performance of straight romance, such as that wonderful scene in Ghost Protocol when Cruise fakes a passionate kiss with Paula Patton’s Jane for the job. And it is truly for the job. So while I appreciate how Rogue Nation gives us the first all-male IMF, Ilsa’s presence still seems both necessarily and productive for Cruise, not to mention Ethan.

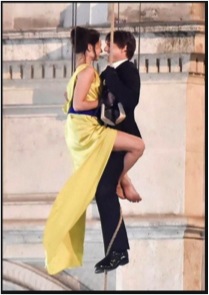

Schnepf: The film often depicts Ethan and Ilsa clinging to life by clinging to each other. So many scenes illustrate this (think of Ethan saving Isla by rappelling off the roof of the Vienna opera house, Ilsa saving Ethan in the Torus-shaped underwater vault, and finally, Ethan saving Ilsa by becoming a human shield on the banks of the Thames). This back-and-forth seems especially strategic for two stateless spies who can no longer count on their countries to protect them. Ethan and Ilsa’s straddling of minds and limbs becomes a visual shorthand for human cooperation, a elegant iteration of the more diffuse assemblage of brains (technological expertise and administrative know-how) and bodies (physical prowess) that imbricates Ethan’s life with the lives of Benji, Brandt, and Luther.

Schnepf: The film often depicts Ethan and Ilsa clinging to life by clinging to each other. So many scenes illustrate this (think of Ethan saving Isla by rappelling off the roof of the Vienna opera house, Ilsa saving Ethan in the Torus-shaped underwater vault, and finally, Ethan saving Ilsa by becoming a human shield on the banks of the Thames). This back-and-forth seems especially strategic for two stateless spies who can no longer count on their countries to protect them. Ethan and Ilsa’s straddling of minds and limbs becomes a visual shorthand for human cooperation, a elegant iteration of the more diffuse assemblage of brains (technological expertise and administrative know-how) and bodies (physical prowess) that imbricates Ethan’s life with the lives of Benji, Brandt, and Luther.

Hu: Michel Serres could have a field day with the assemblages in M:I. When it comes to Ethan clinging to other agents–human or technological–Ethan is usually the parasite. Ethan riding the AirBus: parasite. Ethan on the Burj Khalifa: parasite. Ethan in the chunnel: parasite. Ethan and Ilsa: still mostly parasite, but also, sometimes host! At one point, Ilsa tells Ethan that she’s now saved his life twice but, I think, at the time of the scene, it’s actually be three times? Is Ilsa cancelling out one of the three because Ethan has also been saving her life? Or are they just mutually saving each other’s lives so often that they’ve lost count at this time?

Schnepf: The physical act of hanging on is also an apt metaphor for Ethan’s emotional strategy: cling until you’re let in. He applies it to people the same way he applies it to the A400.

Hu: It speaks so beautifully to his exquisite desperation! One of my favorite things about Cruise is how hard he tries, how persistent and intense he simply is. If Nike hadn’t already done it, I feel like “Just Do It” would be Tom Cruise’s catchphrase. Instead, it’s “One of these days you’re gonna take it too far.”

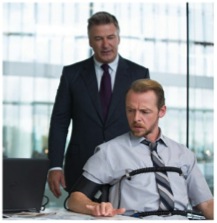

Schnepf: It’s also worth noting that M:I films have represented living in tandem through linked bodies before—Ethan awakening to protect Julia in M:I3 is one example that comes to mind–but what’s interesting about Rogue Nation is that such cooperative endeavors now constitute a formidable, and maybe even superior, alternative to the bureaucracy as a mode of human organization. In their efforts to manage vast numbers of people, the film suggests, state agencies and syndicates alike become hobbled by their dependence on technological innovation. That’s the basic moral behind linking up Benji to all those machines at CIA headquarters. As ready video game consoles, computers undermine productivity from within, while lie detectors fail to suss out the truth about Benji’s bond with Ethan.

Schnepf: It’s also worth noting that M:I films have represented living in tandem through linked bodies before—Ethan awakening to protect Julia in M:I3 is one example that comes to mind–but what’s interesting about Rogue Nation is that such cooperative endeavors now constitute a formidable, and maybe even superior, alternative to the bureaucracy as a mode of human organization. In their efforts to manage vast numbers of people, the film suggests, state agencies and syndicates alike become hobbled by their dependence on technological innovation. That’s the basic moral behind linking up Benji to all those machines at CIA headquarters. As ready video game consoles, computers undermine productivity from within, while lie detectors fail to suss out the truth about Benji’s bond with Ethan.

The Syndicate similarly hitches its fate to the digital. Lane’s crucial mistake, it turns out, is his assumption that data storage is a high-tech affair. In other words, Lane falls into a classic Mission: Impossible trap. He forgets that obsolete technologies still work perfectly fine. By memorizing bank account information, Ethan shows Lane (and us) that, although he’s no USB, he can improvise its function. And in a world where states can disavow their own, Ethan realizes that becoming monetizable data offers a temporary respite from his precarious status.

Hu: Wow, Ethan figures as the information bomb by the end of the film. (Also, did your entire theater laugh when Alec Baldwin says, “Ethan Hunt is the literal manifestation of destiny”??) I’m so glad you brought it back to obsolete technologies, and how they don’t just have decoy or substitute, but real communicative powers in these films. Rogue Nation pays a delightful tribute to the Bruce Geller 60s TV series, where the pilot episode shows Steven Hill’s Dan Briggs (the OG Ethan Hunt) receiving IM information from a vinyl record in a private listening room. Not quite Kittler’s gramophone, but the vinyl certainly conveys more than just jazz in this scene. It’s a fun nugget for anyone invested in the TV series, but it also sets them up: while Briggs leaves unscathed in the original, the vinyl record here is a trap from the Syndicate. Now locked in a listening booth rigged with nerve gas, Ethan faints and is captured. But by having the terrorist Syndicate network use the exact same technology as, quite literally, the Cold War IMF, Rogue Nation tells viewers quite early on that the Syndicate is simply a kind of inverse IMF. As such, the IMF is irrelevant and made-up insofar as the film’s terrorist network is. And the logic of their association gets played out repeatedly in the film through masks, Ilsa, and a DOPE final scene where the IMF captures the Syndicate by locking them in a nerve gas container.

Hu: Wow, Ethan figures as the information bomb by the end of the film. (Also, did your entire theater laugh when Alec Baldwin says, “Ethan Hunt is the literal manifestation of destiny”??) I’m so glad you brought it back to obsolete technologies, and how they don’t just have decoy or substitute, but real communicative powers in these films. Rogue Nation pays a delightful tribute to the Bruce Geller 60s TV series, where the pilot episode shows Steven Hill’s Dan Briggs (the OG Ethan Hunt) receiving IM information from a vinyl record in a private listening room. Not quite Kittler’s gramophone, but the vinyl certainly conveys more than just jazz in this scene. It’s a fun nugget for anyone invested in the TV series, but it also sets them up: while Briggs leaves unscathed in the original, the vinyl record here is a trap from the Syndicate. Now locked in a listening booth rigged with nerve gas, Ethan faints and is captured. But by having the terrorist Syndicate network use the exact same technology as, quite literally, the Cold War IMF, Rogue Nation tells viewers quite early on that the Syndicate is simply a kind of inverse IMF. As such, the IMF is irrelevant and made-up insofar as the film’s terrorist network is. And the logic of their association gets played out repeatedly in the film through masks, Ilsa, and a DOPE final scene where the IMF captures the Syndicate by locking them in a nerve gas container.

Schnepf: The focus on the old is familiar, isn’t it? While Ghost Protocol worried that the project of the spy film had come to an end along with the cold war, Rogue Nation celebrates the spy film because it’s out of date, even suggesting that there’s something to be gained by savvy readers who anticipate the tropes and recognize the limitations of the genre. The movie toys with spy genre expectations by returning to its usual destinations—London, Cuba, Casablanca. It also revels in old media by calling up a host of distinctly “retro” arts—jazz, opera, classical music, drawing by hand. (And collaging? I don’t know. I think it counts. Ethan is obsessed with paper: tickets, photos, maps, newspaper clippings, manila envelopes–all artifacts of pre-digital print culture.)

In any case, the art of the spy film is celebrated and scrutinized. Alec Baldwin’s CIA director fails to appreciate the old-fashioned. For him, the IMF is a woefully antiquated institution, a failed “throwback” to a different era. Of course, this criticism applies to the films as well so suggesting, as he does, that “the time has come to dissolve the IMF” is tantamount to shuttering the Mission: Impossible franchise too. The savviest reader turns out to be Ethan Hunt. The genre’s influence, he realizes, informs the prevailing reliance on gadgetry and he understands how to work that to his advantage.

Hu: The film is also very good about shilling to the massive Chinese film market. When Hunt is first captured by the Syndicate, he wakes up hanging from his wrists in a torture-but-don’t-kill situation–it has all the media aesthetics of terrorism, but the fight itself is, again, a kind of “throwback” grounded expressly in martial arts tactics. Rogue Nation begins with everyone Kung Fu Fighting (a song, by the way, that probably doesn’t have a single Chinese person associated in its production). And it sets a convincing first tone that, while the film doesn’t entirely follow, at least plays up in the subsequent Turandot scene. Jenn, I loved the Turandot sequence. The flute gun! Rebecca Ferguson’s Asian-inspired slitted yellow dress! Benji’s mistake prompted by the fact that two white men kind of look the same! The gunshot that comes during a crescendo (another callback to Hitchcock, this time the cymbal-punch The Man Who Knew Too Much)! I mean, Turandot–an opera by a very non-Chinese person–is literally supposed to take place in China. Omg the stylized drama is all too perfect. As a Chinese person, I give this film a 10/10, would definitely see again.

Schnepf: I wonder, too, about what the film is doing with gender. Ethan’s friends are skeptical of Ilsa and aren’t sure she can be trusted. But they’re a bit too quick to read her through the James Bond lens of woman as femme fatale. What’s quite new, I think, is that Ethan sees her as a highly-trained worker like himself. This assessment, which turns out to be right, overturns the generic expectation that women conform to type as a matter of course. He realizes she’s duplicitous because of her job not her gender.

Hu: There’s a strange scene where Luther points to Ethan’s sketch of Ilsa as proof that he trusted her. From what I gather, it’s the sketch’s detail–complete with Ferguson’s distinct freckles–that leads Luther to read, correctly, into Ethan’s orientation toward Ilsa. But it’s still an odd moment. As the films become less insistent on Hunt having a love interest, they’re also working out how we are to read his particular relationship to women. Indeed, if friendship is the moral of Rogue Nation, it actually works to distract from the romance between Cruise and Pegg.

Schnepf: And, from a certain perspective, it’s possible to see the film’s investment in emotional work over and above bureaucratic work as an allegory about moviemaking too. The film’s plot proposes that bureaucracies live off of a faith in and an insatiable need for new forms of technology. While it’s true that production companies are corporate entities, organizing people through bureaucratic systems of management, that’s not the narrative the makers of Mission: Impossible are interested in telling about their work lives. As Tom Cruise would have it, Skydance Productions and Bad Robot—the corporate entities responsible for Rogue Nation–have found another way, a better way, and even a distinctly unbureaucratic way to organize bodies that embraces people not the technology that replaces or manages them. This goes some way to explaining the relentless reminders we received that Cruise performed all his stunts, that the production refused to rely on CG, that the soundtrack relied exclusively on a live orchestra and shunned electronic equipment. It also makes sense of the way McQuarrie and Cruise describe their collaborative working relationship. I listened to a recent podcast in which McQuarrie described Cruise by revealing that, “Tom works in waves of pure emotion,” while Tom described his relationship with his director by saying, “if he feels strongly about something I’ll do it,” because “we’re in this together.” By this account, movies are made through an amalgam of one’s own feelings and the feelings of others. Is this moviemaking as friendship?

Hu: I love any reading that recuperates Tom Cruise back into sociality, but I’ll play reactionist here and consider the possibility that the film does not thematize Ethan’s functionality so much as his insane luck. And, of course, Ethan’s luck is also Cruise’s. How did someone as wacky as Tom Cruise become as big of a moviestar as he is, or, certainly, was? It’s still kind of incredible. Rogue Nation retroactively suggests that all prior M:Is are, in fact, a product not of organization, but of chance, accidents and implausible probabilities. And, as such, Baldwin’s CIA director insists it’s no longer a viable investment for America. Further, the movie is self-conscious as hell about the spy genre’s reliance on nick-of-time plot twists, and that this might be the last time Cruise’s IMF can pull it off. “We’ve never met before, right?” says Ethan to Ilsa, and at that point they haven’t, but also, in a way, they have.

Schnepf: It’s as though he’s figured out how to harness accidents. This gets played out in the end, I think, when Ethan seems injured. He limps through the London streets as Lane closes in. But it turns out to be a calculated ploy, one shrewdly designed to draw Lane into the magic box that seals his fate. The box offers a final throwback, recalling the 1969 technology of Mission: Impossible’s “The Glass Cage” episode: a glass-panelled holding cell that–like the record store room and the English phone booth that feature prominently in the film–recasts the booths we listen in as torture chambers. It’s curious that the fate Rogue Nation imagines for its villain is to listen to and look at Ethan on the other side of a transparent screen. Is it possible to read the ending as an apt account of our relationship to Cruise? Despite what The Atlantic recently described as a “challenging year for the actor,” his shaky public persona has nonetheless lured many of us into the dark box of the movie theater to listen to Cruise recite his lines on the screen. Rogue Nation had the third largest opening box office of Cruise’s career. In other words, he’s still winning where it counts, despite repeated claims he’s washed up–too committed to Scientology, and too old to be an action hero. So maybe?

Jane Hu: Theater Kid

Jennifer Schnepf: Tweets on Occasion