It’s May, which means it’s time to start thinking about your summer jam. Maybe you think this is premature. But the thing about the summer jam is that it’s not about the summer. The summer jam is an alluring dream of what your summer might be, or an elegy for what your summer might have been, or some combination of the two: a fantasy about nostalgia. The summer jam is about any summer other than the summer you actually have.

Consider this: unlike the summer hits of the 1960s (the Beach Boys’ “All Summer Long,” Martha and the Vandellas’ “Dancing in the Street,” The Lovin’ Spoonful’s “Summer in the City,” the countless songs from beach party movies), the modern summer jam rarely takes the summer as its subject. It is tempting to read this as a histor ical shift in feeling historical. The summer jam as a contemporary phenomenon seems born of certain characteristically post-60s experiences of belatedness, feeling stalled, and otherwise not having your moment. DJ Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince’s 1991 song “Summertime” is the exception to this rule, perhaps because it came early in the summer jam’s history. Given that asynchrony defines the new summer jam, it is difficult to say when exactly it first emerged, but the early 1990s seem about right. The proximity to the end of the millennium would suit the summer jam’s affinity for finitude, its longing for the memory of something. New York City hip hop station Hot 97 held its first Summer Jam concert in 1994, and while the Summer Jam concert is not the same as a summer jam (in fact, in its immediacy and unrepeatability as an event, it runs counter to the genre’s historicizing spirit), presumably the currency of the term roughly indexes the rise of the genre.

ical shift in feeling historical. The summer jam as a contemporary phenomenon seems born of certain characteristically post-60s experiences of belatedness, feeling stalled, and otherwise not having your moment. DJ Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince’s 1991 song “Summertime” is the exception to this rule, perhaps because it came early in the summer jam’s history. Given that asynchrony defines the new summer jam, it is difficult to say when exactly it first emerged, but the early 1990s seem about right. The proximity to the end of the millennium would suit the summer jam’s affinity for finitude, its longing for the memory of something. New York City hip hop station Hot 97 held its first Summer Jam concert in 1994, and while the Summer Jam concert is not the same as a summer jam (in fact, in its immediacy and unrepeatability as an event, it runs counter to the genre’s historicizing spirit), presumably the currency of the term roughly indexes the rise of the genre.

That said, to call the summer jam a genre is a bit of a misnomer. There is no formula for it. A summer jam is made, not born. But there are some basic criteria that may contribute to a song’s ascension to summer jam.

First, the summer jam is popular. There’s no such thing as a connoisseur’s summer jam. There might be a song that perfectly captures your personal experience of summer, but the summer jam is about the failure to capture personal experience. As such, it can never be yours.

Second, the summer jam is ephemeral. You will rarely find a summer jam in someone’s top five songs of all time. Do you remember Lumidee’s “Never Leave You (Uh Oooh, Uh Oooh)” from 2003? No? Even though the video features the actor who played Bodie on The Wire? Maybe that’s because there was hardly anything to it: a dancehall rhythm clapped out like a playground rhyme, and Lumidee singing over it in a voice so slight and remote she might be singing along to a Walkman. But for all those reasons it was a perfect summer jam. Chamillionaire’s “Ridin,’” from 2006, is musically more substantial but makes emptiness its punchline. “They see me rolling / They hating / Patrolling / And trying to catch me ridin’ dirty,” Chamillionaire begins, but in the end he reveals the image of a car filled with guns, alcohol, and drugs to be a mirage created by racial profiling: “I ain’t even ridin’ dirty.” Replete with possibility that is never realized, Chamillionaire’s ride turns out to be an inspired metaphor for summer.

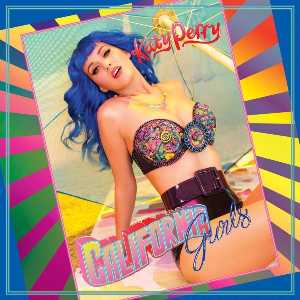

Third, the summer jam has a seemingly inappropriate strain of melancholy. It often seems to be mourning something that’s hardly begun. My summer jam of 2011, Miguel’s “Sure Thing,” promises the beginning of a relationship (“If you be the cash, I’ll be the rubber band / You be the match, I will be your fuse”), but its claustrophobic, minor-key tone sounds like the end of one. Although the verses fantasize about what could be, its chorus shifts into a more anxious mood of preservation: “Even when the sky comes falling / Even when the sun don’t shine / I got faith in you and I.” There’s just enough tension between Miguel’s “faith in you and I” and his insistence that “This love is a sure thing” to make you realize that what makes the song so romantic is that the love might already be gone. A slow jam like “Sure Thing” is not quite typical, though. More often, the summer jam’s melancholy comes in a stranger mode: the depressing party song. Katy Perry’s “California Gurls” was a 2010 summer jam not just because it was about Daisy Dukes, bikinis, and melting popsicles, but because the plinky-plonky synths and Perry’s listless delivery made none of these selling points of summer sound convincing. Its beat is slightly too slow, dragging the song when the lyrics want to bounce. A similar combination of giddy lyrics and moody tone characterizes last year’s “Get Lucky,” by Daft Punk. It seems to issue its invitation to stay up all night and toast the stars from the hangover that follows.

Fourth, the summer jam bends time. It can’t be a coincidence that so many summer jams feature throwback guests: Krayzie Bone from Bone Thugs-n-Harmony on “Ridin,’” Snoop Dogg on “California Gurls,” Niles Rodgers from Chic on “Get Lucky.” In “California Gurls” Katy Perry even gives a shout-out to “Gin and Juice,” released in 1994, when she was nine years old. Although Perry announced the song’s release by tweeting “SUMMER STARTS NOW!,” Snoop Dogg’s presence suggests—with all due respect—that it’s already over. To be clear, this is not a criticism of the song but the source of its appeal. It is what makes the song’s other pop music reference, to Big Star’s “September Gurls,” plausible. Big Star made a career (or failed to do so) out of anachronism. Musically they looked backwards to the 1960s in the 1970s; lyrically they looked backwards to adolescence in songs like “Thirteen” and “Back of a Car”; and in “September Gurls” they sang a kind of love song for nostalgia itself. Who knows what a September gurl is, but the metaphor ties her desirability to the end of something—specifically, to the end of summer, especially seen from even further away, through the eyes of “December boys.” To the extent that “California Gurls” recognizes “September Gurls” as a prefiguration of the summer jam it will itself become, it actually makes sense as a tribute. And because reportedly Perry, at the behest of her manager, changed the title’s spelling after Big Star frontman Alex Chilton’s death in March of 2010, the song starkly exemplifies the elegiac qualities of the summer jam.

Fourth, the summer jam bends time. It can’t be a coincidence that so many summer jams feature throwback guests: Krayzie Bone from Bone Thugs-n-Harmony on “Ridin,’” Snoop Dogg on “California Gurls,” Niles Rodgers from Chic on “Get Lucky.” In “California Gurls” Katy Perry even gives a shout-out to “Gin and Juice,” released in 1994, when she was nine years old. Although Perry announced the song’s release by tweeting “SUMMER STARTS NOW!,” Snoop Dogg’s presence suggests—with all due respect—that it’s already over. To be clear, this is not a criticism of the song but the source of its appeal. It is what makes the song’s other pop music reference, to Big Star’s “September Gurls,” plausible. Big Star made a career (or failed to do so) out of anachronism. Musically they looked backwards to the 1960s in the 1970s; lyrically they looked backwards to adolescence in songs like “Thirteen” and “Back of a Car”; and in “September Gurls” they sang a kind of love song for nostalgia itself. Who knows what a September gurl is, but the metaphor ties her desirability to the end of something—specifically, to the end of summer, especially seen from even further away, through the eyes of “December boys.” To the extent that “California Gurls” recognizes “September Gurls” as a prefiguration of the summer jam it will itself become, it actually makes sense as a tribute. And because reportedly Perry, at the behest of her manager, changed the title’s spelling after Big Star frontman Alex Chilton’s death in March of 2010, the song starkly exemplifies the elegiac qualities of the summer jam.

But the summer jam does not solely look backwards. It looks forward to looking backwards. If Jacques Lacan had listened to summer jams—which he definitely would have done—he would point out that the summer jam speaks in the futur antérieur tense, which describes what will have been. The summer jam promises, “This is the summer you will have had.” For Lacan, the futur antérieur characterizes the fundamental temporal paradox of the subject: “What is realized in my history is not the past definite of what was, since it is no more, or even the present perfect of what has been in what I am, but the future anterior of what I shall have been for what I am in the process of becoming.” Or as Daft Punk puts it in “Get Lucky,” “Our ends were beginnings.” Living in the future anterior means that we can never be fully present to our own history, which is always arriving from the future, nor can we ever be fully present to ourselves. To quote Daft Punk again, “The present has no rhythm.” Instead, the subject structures herself in “anticipated belatedness,” in Samuel Weber’s words. For Lacan, “anticipated belatedness” is our resting state. But the pleasure and poignancy of the summer jam come from its ability to externalize this imperceptible condition and make it into an aesthetic experience. Rather than demanding we live in the present, the summer jam invites us to anticipate our nostalgia for it. In doing so, it also invites us to imagine the subjects summer will have made us—the subjects we are not yet and never will be but always could have been.

Perhaps no song has captured the summer jam’s disjointed temporality better than Carly Rae Jepson’s “Call Me Maybe.” First released as a single on September 20, 2011, it entered the Billboard top 10 in mid-April of 2012, then reached number 1 the week of June 23 and held the position for nine weeks. I don’t think “Call Me Maybe” became 2012’s summer jam because it stayed at number 1 for so long. It stayed at number 1 because it had announced itself as a summer jam. Partly it was the music: with its clipped, almost skeletal verses bursting into the ebullient sweetness of the chorus, the song’s build-ups and let-downs educate listeners in the desire for loss. Partly it was the lyrics, which almost seem to thematize the summer jam. There are the summertime glimpses of skin on a “hot night,” but more than that, there’s the time-warped refrain that conjoins past and future in a kind of Mobius strip: “Before you came into my life / I missed you so bad.” And if the song’s title is syntactically confusing—with no comma, it sounds more like an introduction (cf. “Call me Ishmael”) than an invitation—it is a useful gloss on the Lacanian subject of the futur antérieur, whose self-identity is impossible. It’s hard not to attribute Jepson’s gift for the summer jam to her own discontinuous temporalities. Twenty-six when she released a perfect specimen of teen pop, she was herself living out the anachronism that belongs to the summer jam.

What the summer jam teaches us is that the best way to enjoy your summer is to enjoy your prospective retrospection of it. So in the next few weeks, as you open the windows, put away your coats, and prepare yourself for the summer to come, also remember to prepare yourself for the summer that will have been.

—Lara Langer Cohen: Still not a player

Lara Cohen for Avidly!